When asking people what their favorite

Disney movie is, there are a few movies that come up so frequently that they

have reached the pantheon of “elite” – The

Lion King, Cinderella, Toy Story, and recently, Frozen.

However, there is always the adventurous soul who is

willing to suggest something not quite so obvious. Mulan or Peter Pan,

anyone?

I always wondered what it was about two of my favorite films, The Rescuers and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (see, the fact that your jaw is hanging open that these are someone's favorite Disney films proves exactly my point), that makes them an unpopular, or easily

forgotten, choice amongst Disney lore for the category of “favorite film." I

decided to look at patterns between those two films in order to provide a reason for why people think they are the worst.

Disney’s The Rescuers and The

Hunchback of Notre Dame are some of the darkest of the Walt Disney animation films because they are about an abusive relationship between

orphans and their kidnappers. The villain is not the random dragon-witch who gets upset when she doesn't get invited to a party (Maleficent's freak-out). The villain is the exact person the audience expects to love the hero more than anything else.

So what happens in these two movies? Well, The Rescuers follows two mice who receive a message asking for help from a young orphan girl named Penny. Penny has been kidnapped by a woman named Medusa. She has taken Penny to a hidden swamp where Medusa believes a massive diamond is hidden. She forces Penny to work every night finding this diamond, and Penny nearly drowns in the process. Eventually, the two mice rescue Penny from the swamp and Penny ends up adopted and everyone is happy. Or are we? We just spent two hours watching a young girl get abused by an adult? I guess I'm supposed to feel great about that?

The Hunchback of Notre Dame is about a Catholic archbishop named Frollo. He is trying to rid the world of sin, and so attempts to murder a young, ugly child. Eventually, he feels bad for having tried to do this and so he adopts the child (who he names Quasimodo) and raises him.However, because Quasimodo is so deformed he locks him up in a church tower and refuses to let him interact with the world. When he is locked up, Frollo abuses Quasimodo emotionally and physically. Eventually, with the help of a bad-ass gypsy girl named Esmerelda, Quasimodo escapes from Frollo (who ultimately descends into a pit of fire which is clearly the gates of Hell. Yay fun, light-hearted Disney!)

Okay, okay. So maybe Medusa and Frollo are not technically Penny and Quasimodo's parents. But they act as guardians, and even go so far as to give themselves a title of mom or dad. And maybe Quasimodo is not technically a child. But he is so stunted emotionally and physically, that he comes across as child-like.

Because

these guardian-child relationships fly so directly in the face of the loving, nurturing

parental relationships that we tend to see across films, the shock in a broken

pattern reinforces the tragedy of the on screen events to the audience. In

making the victims innocent children who seem completely defenseless, Disney

created villains so unbearably dark to the audience that the movies become lost

to history.

The Rescuers and The Hunchback of Notre Dame have villains that are too unexpected for the audience to handle. As Lynda Haas explains, films have a tendency to depict mothers as a “silent and suffering woman” (the mother as a sacrificial lamb willing to do

anything for her child). This “sacrificial lamb” role has resulted in the audience frequently

defining women based on how they treat their children. Haas says that, in

movies, “a mother’s identity is relational,” as this identity is based on others’,

specifically a child’s, successes. But in contrast to this expected

pattern of identity loss, Medusa uses Penny to serve her own whims, as oppose

to other “true” mothers from movies that would break their back serving their

child’s every whim. The audience recognizes that Medusa could never fill the

role of the mother Penny wishes for, as she is clearly ambivalent toward

Penny’s life and does not fit the category that Lynda Haas has laid out

for us.

Medusa deviates an expected pattern of film to such an extent, that The Rescuers leaves an

audience shocked, and unable to reconcile the "mother" character they are not used to seeing on screen. Similarly, the "father" figure in The Hunchback goes against what the audience expects. As Sarah Boxer argues, fathers are much more present across films than mothers. And the result of erasing mothers? Boxer's answer - "the newest beneficiary of the dead mother: the good father." She is correct, because most animated films lack a mother character entirely, and the father always rises to the occasion as a "hero" for the son/daughter. I mean, just think about the many great dad/son dramas out there. Disney itself produced one of the greatest.

So when the emotional and physical abuse is much greater than the "No Dad, I'm giving up on your dream" line, audiences can't reconcile the broken pattern. And they rejected The Hunchback because of that.

The violent

relationship in The Rescuers and The Hunchback of Notre Dame is far too extreme

for the audience to feel comfortable viewing it as entertainment. It is not a

relationship between two individuals who could, in some scenarios, be seen as

evenly matched. So next time you give your "The Lion King" answer when asked your favorite Disney movie, be rest assured. You might be basic, but you are likely too discomforted by abuse, and that is honestly not a bad thing.

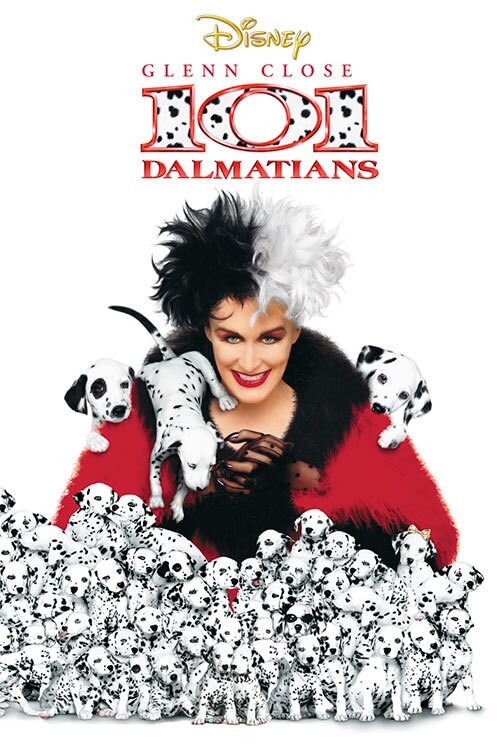

* Okay, it is pretty cheap that I'm starting with a live action movie that was technically not a remake. But this is one of the most iconic Disney live-action movies, and will forever be one of the staples in Walt Disney lore.

* Okay, it is pretty cheap that I'm starting with a live action movie that was technically not a remake. But this is one of the most iconic Disney live-action movies, and will forever be one of the staples in Walt Disney lore.

4) Alice in Wonderland

4) Alice in Wonderland 5) Maleficent

5) Maleficent